Potential Activities and Long Lifetimes of Organic Carbon-Degrading Extracellular Enzymes in Deep Subsurface Sediments of the Baltic Sea

Abstract

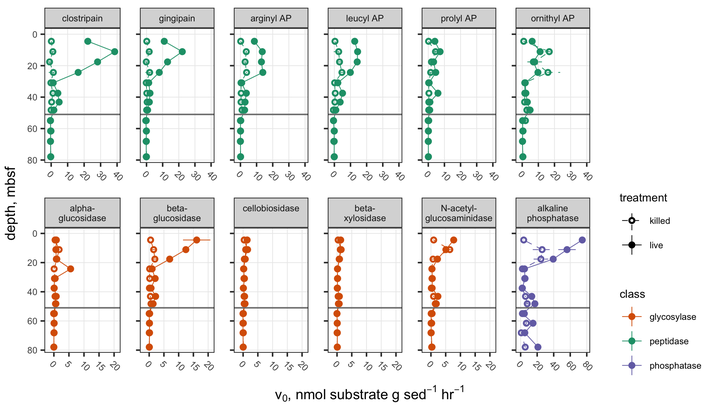

Heterotrophic microorganisms in marine sediments produce extracellular enzymes to hydrolyze organic macromolecules, so their products can be transported inside the cell and used for energy and growth. Therefore, extracellular enzymes may mediate the fate of organic carbon in sediments. The Baltic Sea Basin is a primarily depositional environment with high potential for organic matter preservation. The potential activities of multiple organic carbon-degrading enzymes were measured in samples obtained by the International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 347 from the Little Belt Strait, Denmark, core M0059C. Potential maximum hydrolysis rates (Vmax) were measured at depths down to 77.9mbsf for the following enzymes: alkaline phosphatase, β-D-xylosidase, β-D-cellobiohydrolase, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, β-glucosidase, α-glucosidase, leucyl aminopeptidase, arginyl aminopeptidase, prolyl aminopeptidase, gingipain, and clostripain. Extracellular peptidase activities were detectable at depths shallower than 54.95mbsf, and alkaline phosphatase activity was detectable throughout the core, albeit against a relatively high activity in autoclaved sediments. β-glucosidase activities were detected above 30mbsf; however, activities of other glycosyl hydrolases (β-xylosidase, β-cellobiohydrolase, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, and α-glucosidase) were generally indistinguishable from zero at all depths. These extracellular enzymes appear to be extremely stable: Among all enzymes, a median of 51.3% of enzyme activity was retained after autoclaving for an hour. We show that enzyme turnover times scale with the inverse of community metabolic rates, such that enzyme lifetimes in subsurface sediments, in which metabolic rates are very slow, are likely to be extraordinarily long. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests enzyme lifetimes are, at minimum, on the order of 230days, and may be substantially longer. These results lend empirical support to the hypothesis that a population of subsurface microbes persist by using extracellular enzymes to slowly metabolize old, highly degraded organic carbon.

This paper is the culmination of several years of lab and fieldwork, mostly performed by students in my lab. Shane Hagen and Katherine Mulligan were at the time undergraduates (both subsequently enrolled in medical school), Richard Kevorkian and Austen Webber were post-bac technicians (both subsequently enrolled in graduate school) and Jenna Schmidt and Taylor Royalty were MS and Ph.D. students, respectively, in my lab. This paper used detailed characterization of extracellular enzyme activities in estuarine sediments to show two things that were not previously known: a.) heterotrophic microbes in subsurface sediments use extracellular enzymes to access detrital organic matter, and that b.) microbes in deeper sediments express enzymes that are adapted to more highly-degraded organic matter. The second point contributes to a major debate in subsurface microbiology about the extent to which subsurface microbes are adapted to their environment. Since most of these organisms are in a non-growing state in marine sediments, it has been argued that they are not adapted to live in this environment. Our paper suggests that, counterintuitively, they may be adapted to respond to environmental changes during burial.