Analytical and Computational Advances, Opportunities, and Challenges in Marine Organic Biogeochemistry in an Era of “Omics”

Abstract

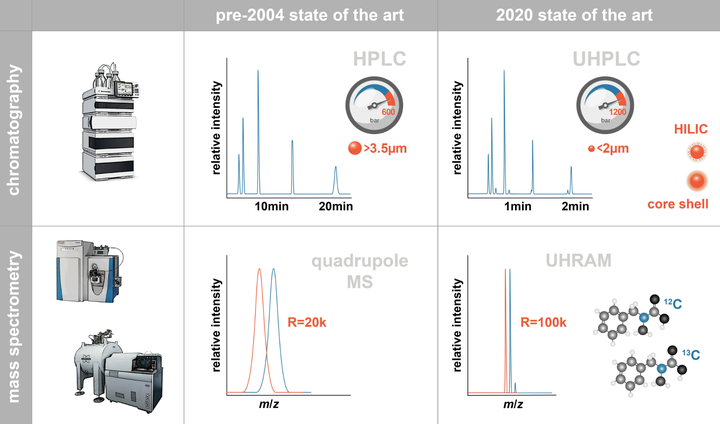

Advances in sampling tools, analytical methods, and data handling capabilities have been fundamental to the growth of marine organic biogeochemistry over the past four decades. There has always been a strong feedback between analytical advances and scientific advances. However, whereas advances in analytical technology were often the driving force that made possible progress in elucidating the sources and fate of organic matter in the ocean in the first decades of marine organic biogeochemistry, today process-based scientific questions should drive analytical developments. Several paradigm shifts and challenges for the future are related to the intersection between analytical progress and scientific evolution. Untargeted “molecular headhunting” for its own sake is now being subsumed into process-driven targeted investigations that ask new questions and thus require new analytical capabilities. However, there are still major gaps in characterizing the chemical composition and biochemical behavior of macromolecules, as well as in generating reference standards for relevant types of organic matter. Field-based measurements are now routinely complemented by controlled laboratory experiments and in situ rate measurements of key biogeochemical processes. And finally, the multidisciplinary investigations that are becoming more common generate large and diverse datasets, requiring innovative computational tools to integrate often disparate data sets, including better global coverage and mapping. Here, we compile examples of developments in analytical methods that have enabled transformative scientific advances since 2004, and we project some challenges and opportunities in the near future. We believe that addressing these challenges and capitalizing on these opportunities will ensure continued progress in understanding the cycling of organic carbon in the ocean.

In 2019, Carol Arnosti, Thorsten Dittmar, Kai-Uwe Hinrichs, Cindy Lee, and Stuart Wakeham organized a workshop of organic geochemists at the Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg (Institute for Advanced Study) in Delmenhorst, Germany. I was privileged to serve as the lead author of the Analytical Chemistry working group, in which we discussed advances since the John Hedges Memorial Symposium in 2004^[Coincidentally, this was the first conference I ever attended.], and the opportunities for technological development in marine organic geochemistry over the next decade or so.

2004 was an interesting marker because this roughly corresponds to the period in which ‘omics technologies became accessible to marine organic geochemistry. Marine organic geochemists in 2020 need to be thinking about the inner workings of microbial communities in the ocean (and, indeed, my research has shifted during this period from more-or-less pure geochemistry to bioinformatics). It was interesting to me that the single point of unanimity among the reviewers of this manuscript was the idea that advances in computational techniques and tools, such as git, GitHub, and interpreted languages such as R and python, are critical to the field, so that section was substantially expanded during reviews. Going forward, it is clear that there is no meaningful organic geochemistry without microbial ecology, genomics, and even genetics.

Typically, the flow of information has been primarily from basic microbiology to microbial ecology to organic geochemistry, at least as far as environmental biomarkers are concerned. An unexpected (to me at least) consequence of the union of ‘omics technologies with organic geochemistry is that it allows us to study microbes in their natural environment much more realistically. I’m looking forward to the next seminar in this series, perhaps ten or fifteen years from now. I expect in that time we will have gained many new insights about marine organic geochemistry, but also that the work of marine organic geochemists will have spawned important new findings in microbial physiology and ecology.